I've decided to do a follow-up post to my last one on the Marquis of Worcester. One reason is that from my Blogger statistics I see that a large proportion of visitors are from Europe, accessing my blog via translate.googleuser.content.com. Since I gave an original version of Article 56 of the Century of Inventions, with its old mid-17th century spelling, and that only as an image, I'll give my own modernised text version of it here, along with Article 99.

I also have a bit more to say about Henry Dircks's comments on the Marquis and his inventions.

Articles 56 and 99

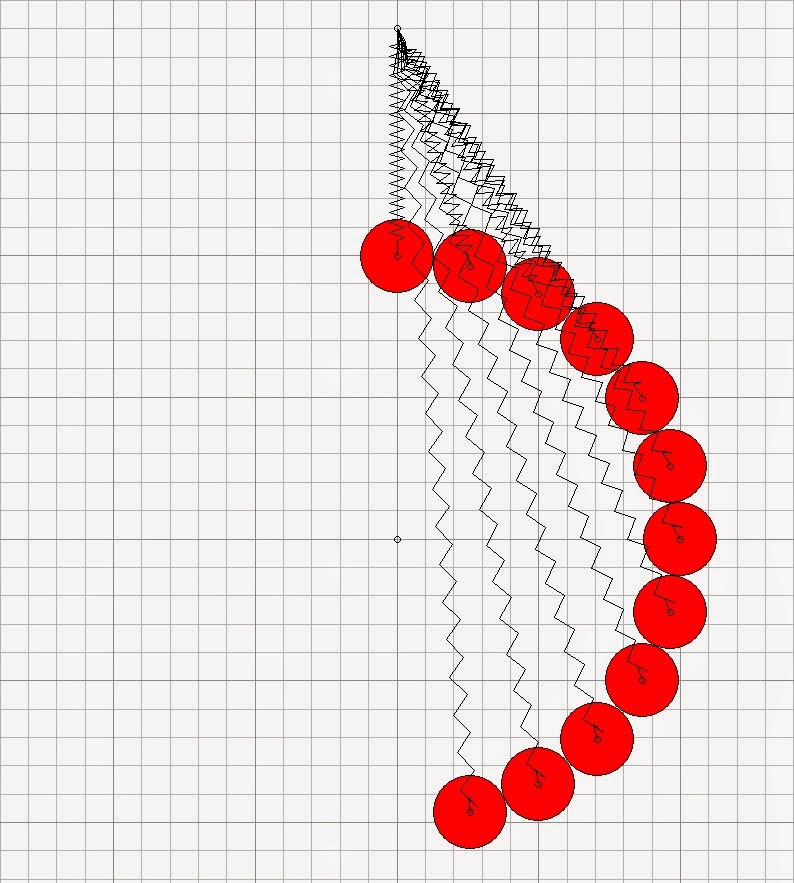

56. To provide and make that all the weights of the descending side of a wheel shall be perpetually further from the center, than those of the [mounting] side, and yet equal in number and heft of the one side as the other. A most incredible thing if not seen, but tried before the late King of happy and glorious memory in the Tower by my directions, two Extraordinary Ambassadors accompanying His Majesty and the Duke of Richmond, the Duke of Hamilton, and most part of the Court attending him. The wheel was 14 feet over, and 40 weights of 50 pounds apiece; Sir William Belford, then Lieutenant of the Tower, and yet living can justify it with several others; they all saw that no sooner these great weights passed the diameter line of the upper side but they hung a foot further from the center, nor no sooner passed the diameter line of the lower side, but they hung a foot nearer; be pleased to judge the consequence.

99. How to make one pound weight to raise a hundred as high as one pound falls, and yet the hundred pounds descending does nothing less than one hundred pounds can effect.

Dircks's comments on the Marquis

Henry Dircks's book with the full title The life, times and scientific labours of the second Marquis of Worcester To which is added, a reprint of his Century of inventions, 1663, with a commentary thereon is the best reference I've seen on the Marquis of Worcester and his inventions. It can be found on-line, e.g. at http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/18929#/summary. I'll list a small sample of Dircks's many interesting comments here, with page references, and some remarks of my own.

p25: "...and Sir William Balfour was at the time Lord Lieutenant of the Tower. Now the latter circumstance would fix the date as not being later than 1641, while other facts make it reasonable to suppose the experiment took place at least two or three years earlier... This wheel experiment may have been made in 1638-9..."

p357: "We have also given in the Life... at page 216, a copy of a [manuscript] list of heads of some inventions, among which occurs:— "Intelligence at a distance communicative, and not limited to distance, nor by it the time prolonged." The "not limited to distance," and the "time not prolonged" appear conclusive. Wires, tubes, or other mechanical means of communication would neccessarily be "limited to distance;" and that which alone we believe to be illimitable through any human agency is electricity. Truly the Marquis of Worcester was a man of no ordinary stretch of mind."

How difficult would it have been to make the essentials of a simple telegraph system in the mid-17th century? Insulated metal wire, an on/off switch, a battery and an electromagnet, would not have been too difficult, always assuming the inventor knew what he was doing. Dircks at least leaves open the possibility that the Marquis and his workman did know.

p358: "He [the Marquis] also touches on his pecuniary position, offering, in case he is assisted with the patronage and support sought, 'to outgo the £6 or £700,000 already sacrificed'..."

Using the currency converter at http://www.measuringworth.com/ukcompare/index.php, we find that even the smaller estimate of £600,000 spent by the Marquis on his inventions converts to a staggering 2.8 billion pounds sterling or 4.71 billion US dollars in today's money. (I used the "per capita GDP" method, which seemed the most appropriate, from a base year of 1659).

p358/9: "He assures Parliament that his several inventions are 'practicable with my directions, by the unparalleled workman both for trust and skill, Caspar Kaltoff's hand, who hath been these five and thirty years as in a school under me employed.'"

Both the Marquis and Dircks describe Kaltoff as a "workman", but a more apt description would be "master craftsman". He was one of the famous German Kaltoff (more usually spelled Kalthoff) family of craftsmen and gunsmiths.

p373: "His 'Century' has been preserved to these times, but all his other works which might have thrown a fuller light on his inventions have perished. Whether books and papers belonging to him were procured and burnt, according to the story relating to such an incident, is now past discovery; but it is abundantly evident that the great scarcity of information which exists, has led to the propagation of many unfounded statements, and given undue weight to others purely conjectural..."

In my last blog post we have already seen the unfounded claim about the internal operating mechanism of the Marquis's wheel, promoted as usual by those who already "know" that perpetual motion is "impossible".